MARRIAGE CUSTOMS

German law states that when a couple decided they were in love and wanted to marry they would obtain from the local priest/pastor the church blessing and with the approval of both families would live together.

Once the woman announced that she was pregnant the parents would organize a wedding with all the celebrations. The wedding feast and subsequent party could last for a week or more.

Up to the year 1848 a bridal pair had to obtain permission to wed, not only from their parents (the age of majority was 24 years) but also from their respective overlord or magistrate – while this permission was nearly always granted it also entailed expenses.

Now procreation was very important and if within seven years the woman did not become pregnant the relationship which was in effect a marriage was annulled and both parties were free to pursue another partner from which a child could be born.

Polterabend – this is an informal (informal dress and food) party at the evening before the wedding where plates and dishes are smashed (the broken pieces are thought to bring good luck to the bride). The bride and groom have to clean up everything.

Kidnapping of the bride – in some areas (mostly in small villages) friends kidnap the bride and the groom has to find her. Normally, he has to search in a lot of pubs and invite all people in there (or pay the whole bill). Sometimes this ritual ends badly.

Wedding Rings: — Germans wear wedding rings on the right hand! And the groom and bride have identical rings (wedding bands – no diamonds)

Wedding Toast:– Jeder sieht ein Stückchen Welt, gemeinsam sehen wir die ganze.” In English that means, “Each of us sees a part of the world; together we see all of it.”

Bride, Silesia. (1859-1860)

|

German bride, Nuremberg.] (1859-1860)![[German bride, Nuremberg.] Digital ID: 817750. New York Public Library [German bride, Nuremberg.] Digital ID: 817750. New York Public Library](http://images.nypl.org/index.php?id=817750&t=r)

|

A married pair leaving church. (1881)

|

Wedding celebration of Germanic tribe

|

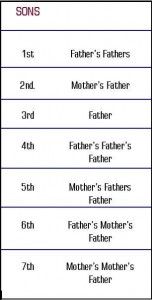

NAMING CUSTOMS

German families often used the following pattern for naming children. Again, though, there were several variations used, and often the pattern was disrupted by other circumstances.

When a duplicate name occurred in these patterns, the next name in the pattern was usually used.

Often when a child died in infancy, his/her name was reused for the next child of the same gender. Too, a child’s name was sometimes repeated when a spouse died and the surviving spouse remarried and had more children.

This would result in half-siblings with the same name.

![]()

BAPTISM CUSTOMS

Two names were usually given to a child at Birth or Baptism. In Germany the first name – what we often refer to as the given name was a spiritual name usually given to honour a favourite saint. The spiritual name was often used repeatedly in families.

Two names were usually given to a child at Birth or Baptism. In Germany the first name – what we often refer to as the given name was a spiritual name usually given to honour a favourite saint. The spiritual name was often used repeatedly in families.

The second name – what we now would refer to as a middle name – was a secular or call name, and was the name by which the person was known.

One of the most common and heavily used saint’s names for males was “Johann” (with no “s”), and for females, “Johanna” or “Anna”.

Thus, in a hypothetical German family, we might see the male children named.

- Johanna Heinrick Riepe

- Johann Hermann Riepe

- Johann Friedrich Riepe

Respectively, these children would be known as:–Heinrich (Henry), Hermann, and Friedrich (Fred).

For girls, we may see:

- Anna Maria Riepe

- Anna Catherine Riepe

- Anna Louise Riepe

Respectively, these children would be known as:– Maria (Mary), Catherine, and Louise.

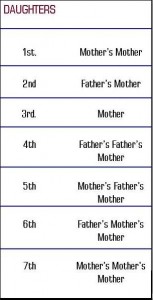

When Life Ended - Information and Picture Supplied by:–Kathy Gosz, Wisconsin, USA and Ernst Mettlach of Germany.(Click to enlarge)

DEATH & BURIEL CUSTOMS

The Germans believed that a human consisted of 2 parts; the “Lika” and the “Saiwalo” (Proto-Germanic) or “Likh” and “Sal” (Old Norse), the Lika (body, corpse) was the mortal body that stayed behind in this world when the person died and the Saiwalo (soul) was the soul that went to the afterlife, the Dutch and German words for “dead body” are still “lijk” and “leiche”, while the Scandinavian languages all use the word “lik”, which are a remnant of this belief.

The Germans also believed in reïncarnation which made them less afraid of death, the only thing they were afraid of was that the dead would come to life again to haunt them, this belief is very old and already existed before the Germans ruled northern Europe, this is proven by (among other things) a Pre-Germanic sword that has been found in a rich gravehill in the Netherlands which was bended and broken before it was laid in the grave as grave-gift to make sure it could not be used by the dead person in case he came alive again.

Spirits of dead persons who did not go to the afterlife but instead stayed in the human world were called “Draugr” in Old Norse, they did not necesserily have to be evil because that depended on how the person was during his mortal life.

When Life Ended

(Information and Picture Supplied by:–Kathy Gosz, Wisconsin, USA and Ernst Mettlach of Germany.)

On the funeral day, the coffin was placed in front of the house and was then brought in a procession through the whole village. The house was decorated as you can see in the picture above.

The crucifix was very important; it was a special crucifix called a “Versehkreuz” in the Trier region. Every household had such a crucifix, and it was only used for burials. “Verseh” comes from the verb “versehen”, which means “to provide”. Two blessed candles stood left and right of this cross, along with a small bowl with blessed water and a palm sprig. (The crucifix in the picture was handmade by Ernst’s grandfather, and it is now in the possession of his mother.

It was again used during the burial of her mother and father.) Today as well as in the past, the church bell rings in the German villages to announce a death. To read this full article Click Here